I. Introduction

A. Definition of Terms:

Bitcoin is a form of digital currency, created and held electronically. No one controls it. Bitcoins aren’t printed, like dollars or euros – they’re produced by people, and increasingly businesses, running computers all around the world, using software that solves mathematical problems.[1]

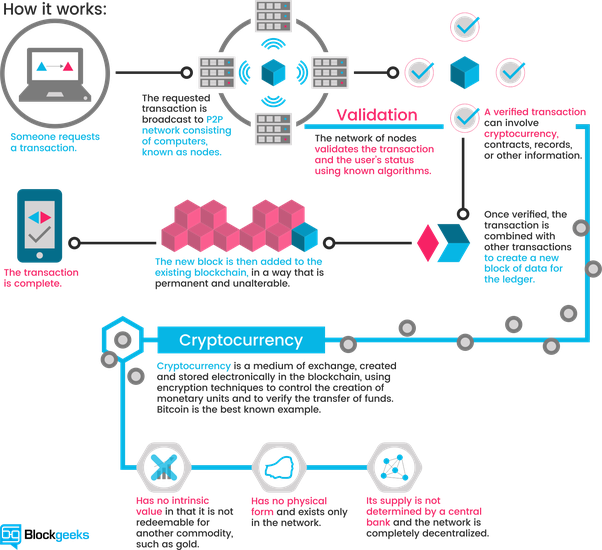

Blockchain is often referred to as a type of distributed ledger technology (DLT) that provided the foundation for bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies when they first emerged. A simple way to conceptualize blockchain, however, is as a permanent ledger which records transactions. However rather than one ledger, there are multiple copies of the ledger in the network called nodes. If a new block of data is to be added to the blockchain, a majority of the nodes within the network, each of which possesses copies of the existing blockchain must verify the proposed transaction. A key feature of this multiple node structure is that it enables unknown counterparties to trade with each other securely and uses a cryptographic key to authenticate participants.[2]

Cryptocurrency is a digital asset designed to work as a medium of exchange that uses cryptography to secure its transactions, to control the creation of additional units, and to verify the transfer of assets. Cryptocurrencies are classified as a subset of digital currencies and are also classified as a subset of alternative currencies and virtual currencies.[3]

Ledger – a book or other collection of financial accounts.[4]

Satoshi Nakamoto is the name used by the unknown person or people who designed bitcoin and created its original reference implementation. As part of the implementation, they also devised the first blockchain database. In the process they were the first to solve the double-spending problem for digital currency. They were active in the development of bitcoin up until December 2010.[5]

B. The Blockchain Concept

Blockchain technology is not a new technology. Rather, it is a combination of proven technologies applied in a new way. It was the particular orchestration of three technologies (the Internet, private key cryptography and a protocol governing incentivization) that made bitcoin creator Satoshi Nakamoto’s idea so useful.[6]

| Blockchains are built from three (3) technologies | ||

| 1. Private Key Cryptography | 2. Peer-to-Peer (P2P) Technology | 3. Program (the blockchain’s protocol) |

| Cash vs. Plastic | Tree falls in a forest | Tragedy of the commons |

| Identity | System of Record | Platform |

The result is a system for digital interactions that does not need a trusted third party. The work of securing digital relationships is implicit — supplied by the elegant, simple, yet robust network architecture of blockchain technology itself.[7]

C. How a Blockchain Works

A blockchain is essentially a distributed database of records or public ledger of all transactions or digital events that have been executed and shared among participating parties. Each transaction in the public ledger is verified by consensus of a majority of the participants in the system. And, once entered, information can never be erased. The blockchain contains a certain and verifiable record of every single transaction ever made. To use a basic analogy, it is easy to steal a cookie from a cookie jar, kept in a secluded place than stealing the cookie from a cookie jar kept in a market place, being observed by thousands of people.

Bitcoin is the most popular example that is intrinsically tied to blockchain technology. It is also the most controversial one since it helps to enable a multibillion-dollar global market of anonymous transactions without any governmental control. Hence it has to deal with a number of regulatory issues involving national governments and financial institutions.[8]

Instead of relying on a third party, such as a financial institution, to mediate transactions, member nodes in a blockchain network use a consensus protocol to agree on ledger content, and cryptographic hashes and digital signatures to ensure the integrity of transactions.

Consensus ensures that the shared ledgers are exact copies, and lowers the risk of fraudulent transactions, because tampering would have to occur across many places at exactly the same time. Cryptographic hashes, such as the SHA256 computational algorithm, ensure that any alteration to transaction input — even the most minuscule change — results in a different hash value being computed, which indicates potentially compromised transaction input. Digital signatures ensure that transactions originated from senders (signed with private keys) and not imposters.

The decentralized peer-to-peer blockchain network prevents any single participant or group of participants from controlling the underlying infrastructure or undermining the entire system. Participants in the network are all equal, adhering to the same protocols. They can be individuals, state actors, organizations, or a combination of all these types of participants.

At its core, the system records the chronological order of transactions with all nodes agreeing to the validity of transactions using the chosen consensus model. The result is transactions that are irreversible and agreed to by all members in the network.[9]

D. Development of Blockchain[10]

The first major blockchain innovation was bitcoin, a digital currency experiment. The market cap of bitcoin now hovers between $10–$20 billion dollars, and is used by millions of people for payments, including a large and growing remittances market.

The second innovation was called blockchain, which was essentially the realization that the underlying technology that operated bitcoin could be separated from the currency and used for all kinds of other interorganizational cooperation. Almost every major financial institution in the world is doing blockchain research at the moment, and 15% of banks are expected to be using blockchain in 2017.

The third innovation was called the “smart contract,” embodied in a second-generation blockchain system called ethereum, which built little computer programs directly into blockchain that allowed financial instruments, like loans or bonds, to be represented, rather than only the cash-like tokens of the bitcoin. The ethereum smart contract platform now has a market cap of around a billion dollars, with hundreds of projects headed toward the market.

The fourth major innovation, the current cutting edge of blockchain thinking, is called “proof of stake.” Current generation blockchains are secured by “proof of work,” in which the group with the largest total computing power makes the decisions. These groups are called “miners” and operate vast data centers to provide this security, in exchange for cryptocurrency payments. The new systems do away with these data centers, replacing them with complex financial instruments, for a similar or even higher degree of security. Proof-of-stake systems are expected to go live later this year.

The fifth major innovation on the horizon is called blockchain scaling. Right now, in the blockchain world, every computer in the network processes every transaction. This is slow. A scaled blockchain accelerates the process, without sacrificing security, by figuring out how many computers are necessary to validate each transaction and dividing up the work efficiently. To manage this without compromising the legendary security and robustness of blockchain is a difficult problem, but not an intractable one. A scaled blockchain is expected to be fast enough to power the internet of things and go head-to-head with the major payment middlemen (VISA and SWIFT) of the banking world.

This innovation landscape represents just 10 years of work by an elite group of computer scientists, cryptographers, and mathematicians. As the full potential of these breakthroughs hits society, things are sure to get a little weird. Self-driving cars and drones will use blockchains to pay for services like charging stations and landing pads. International currency transfers will go from taking days to an hour, and then to a few minutes, with a higher degree of reliability than the current system has been able to manage.

E. What are the Benefits of Blockchain?

In legacy business networks, all participants maintain their own ledgers with duplication and discrepancies that result in disputes, increased settlement times, and the need for intermediaries with their associated overhead costs. However, by using blockchain-based shared ledgers, where transactions cannot be altered once validated by consensus and written to the ledger, businesses can save time and costs while reducing risks.

Blockchain consensus mechanisms provide the benefits of a consolidated, consistent dataset with reduced errors, near-real-time reference data, and the flexibility for participants to change the descriptions of the assets they own.

Because no one participating member owns the source of origin for information contained in the shared ledger, blockchain technologies lead to increased trust and integrity in the flow of transaction information among the participating members.

Immutability mechanisms of blockchain technologies lead to lowered cost of audit and regulatory compliance with improved transparency. And because contracts being executed on business networks using blockchain technologies are smart, automated, and final, businesses benefit from increased speed of execution, reduced costs, and less risk, all of which enables businesses to build new revenue streams to interact with clients.[11]

II. Significance of the Study

This paper provides the basics of blockchain technology and the possible implications in the Philippine legal system. While blockchain have been in existence and growing at an exponential rate in developed countries for more than a decade, it is still in the introduction stage in the Philippine market.[12]

The legal consequences of contracts entered into and the implications to procedural/jurisdictional aspects are analyzed. The discussions could be possible references for policy determination and legislation purposes, particularly on the regulation of blockchain technology.

III. Statement of the Problem

What are the legal implications of security mechanisms on blockchain technology in the enforceability of contracts and in procedural/jurisdictional issues?

IV. Review of Related Literature

A. First World Regulation on Blockchain

While the blockchain technology is already operating for quite some time, state policies and legislative actions have been slow in catching up with the increasing trends of cryptocurrecies. In the U.K., there is currently no specific regulation of the blockchain.[13]

The U.S. federal government has not exercised its constitutional preemptive power to regulate blockchain to the exclusion of states (as it generally does with financial regulation) or even expressed intention to do so, regardless of the interest of federal agencies. And so the states remain free to introduce their own rules and regulations. As an example, although New York did not enact state-wide legislation recognizing blockchain for record-keeping purposes, in June 2015 it became the first state in the U.S. to regulate virtual currency companies through state agency rulemaking.

In 2017, at least eight U.S. States have worked on bills accepting or promoting the use of Bitcoin and blockchain technology, while a couple of them have already passed them into law.

The most important developments for blockchain’s regulation and implementation in the U.S. in an evidentiary context occurred in Arizona (recognition of smart contracts), Vermont (blockchain as evidence), Chicago (real estate records), and, most importantly, Delaware (pending initiative authorizing registration of shares of Delaware companies in blockchain form).

In the U.S., Bitcoin is set to be given the same financial safeguards as traditional assets. The U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission has granted LedgerX, a cryptocurrency trading platform operator, approval to become the first federally regulated digital currency options exchange and clearinghouse in the U.S.[14]

B. Philippine setup

There is no law specifically regulating blockchain technology in the Philippines. However, the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP) through its Monetary Board issued guidelines to regulate the use and exchanges of virtual currencies (VC),[15] Said guidelines include the requirement for VC exchange to register and be issued a Certificate of Registration (COR) to operate as remittance and transfer company pursuant to prevailing rules. One of the reasons for this regulation is the possibility of circumventing the regulation under the Anti-Money Laundering law.[16]

There are currently several VC chains in the Philippines namely https://remitano.com/ph, https://coin.ph, https://www.buybitcoin.ph, https://www.buybitcoinworldwide.com/, and https://coinage.ph among others. These VC chains offer exchanges for Bitcoin. A few offer exchanges for Ethereum or Tether USDT.

In the absence of a special law on blockchain and cryptocurrencies, the Philippines have the consumer act,[17] e-commerce law[18] and the anti-cybercrime law,[19] in addition to the suppletory application of the Civil Code and other laws of general application.

V. Findings

A. Enforceability of Contracts

Contracts are obligatory, in whatever form they may have been entered into, provided all the essential requisites for their validity are present. However, when the law requires that a contract be in some form in order that it may be valid or enforceable, or that a contract be proved in a certain way, that requirement is absolute and indispensable.[20] The right of the parties cannot be exercised if the law requires a document or other special form. In such case, the contracting parties may compel each other to observe that form, once the contract has been perfected. This right may be exercised simultaneously with the action upon the contract.[21] This means that the medium of transaction does not remove it from the definition of a contract and its effects, as long as there is appropriate consent, object, and cause.

The most common transaction using blockchain technology and cryptocurrencies is a contract of sale. Under the Civil Code, the contract of sale is perfected at the moment there is a meeting of minds upon the thing which is the object of the contract and upon the price.[22] The cryptocurrency could be regarded as the consideration since it need not be money or legal tender. Since a contract of sale is likewise covered by the Statute of Frauds,[23] an agreement for the sale of goods, chattels or things in action, at a price not less than five hundred pesos is unenforceable, unless the buyer accept and receive part of such goods and chattels, or the evidences, or some of them, of such things in action or pay at the time some part of the purchase money[24] in the form of cryptocurrency.

Online transactions could be considered “in writing” even if they are in the intangible medium during transaction because it can always be printed upon the will of the parties. But even assuming transactions are not considered “in writing”, the very nature of blockchain technology in producing distributed public ledgers is equivalent to a “sufficient memorandum” as may be covered by Civil Code provision. [25]

However, when the law requires that a transaction be in public instrument, such as acts and contracts which have for their object the creation, transmission, modification or extinguishment of real rights over immovable property,[26] the rules on notarial practice[27] must be complied. This is not possible under the present electronic commence since the “acknowledgment” before a notary public must be in person, in a single occasion, and only after presenting an integrally complete instrument document. Unless the rules on notarial practice is amended, there can be no public instrument that can be conveniently generated through online transaction.

It could be argued nonetheless that the very purpose of notarization is served by the blockchain technology itself. Since the technology is based on transparent duplicate recordings in several online ledgers and databases, the integrity of the transaction as well as the apparent voluntariness of parties in entering into transactions are observed and documented.

B. Procedural/Jurisdictional Issues

Transactions utilizing blockchain technology are usually between and among different countries. These transboundary transactions could bring compounded problems on jurisdiction of courts in case controversy arise.

One of the key selling points of blockchain technology is that it enables an even more integrated approach to cross border transactions as the nodes on a blockchain can be located anywhere in the world. However this poses a number of jurisdictional issues. At a simple level, every transaction potentially comes under the legislative umbrella of wherever a node exists whether in respect of financial services or data protection. The blockchain would then need to be compliant with a potentially unwieldy number of legal and regulatory regimes.

Building on this, in the event of a fraudulent or erroneous transaction, the locus of the relevant “act” could be unclear as the transaction may have occurred simultaneously in a number of different places. This is particularly the case if there are flimsy contractual provisions governing a transaction done across blockchain which would be likely in the case of certain, more novel, transactions. In contrast, however, in a conventional banking transaction if the bank is at fault, irrespective of the transacting mechanism or location, the bank can be sued and the applicable jurisdiction will most likely be contractually governed. A further litigation issue arises where it is the blockchain itself that is the source of the fault. In addition to the ambiguity as to the actual locus of the blockchain, the absence of formalized blockchain standards and providers could potentially leave consumers with no relief. [28]

Players in a blockchain system will – by definition – be ‘distributed’ and are likely to be spread around the globe. Parties will be in a dilemma which laws apply. Even the location of relevant computer server will add to procedural difficulties. The current alternative dispute resolution mechanisms will be tested by its applicability and appropriateness to resolve blockchain issues. For example, might an arbitral award be easier to enforce against an overseas counterparty than a court award? Similarly, how would decisions made by the blockchain community be enforced?

In practice, it would seem advisable for parties to define the applicable law and jurisdiction in advance, perhaps in the ‘terms’ (i.e. code) of the relevant smart contract. Over time, we may see blockchain-based service providers requiring customers to sign up to governing law and jurisdiction in the same way as for websites, i.e. via ‘terms of use’. In the case of a private blockchain, users could be required to sign up to specific terms of service before being granted access to the blockchain solution in question. [29]

VI. Conclusions

The security mechanisms of blockchain technology could be a substitute to several substantive and procedural requirements of commercial transactions. For transactions involving contracts of sale alone, one could utilize the promising features of a “smart contract” which is a computer protocol intended to facilitate, verify, or enforce the negotiation or performance of contract.[30] This means that a computer program may be designed so that it ensures contractual obligations are executed even without human intervention within the parameters set.

But this technology intended for convenience can also be a source legal complications. “Smart contracts”, for instance, present a problem for the forensic exercise of contractual interpretation. Currently, when the meaning of a contract is disputed by the parties to it, a court will consider what that agreement would mean to a reasonable human observer. Where that agreement is written in computer code, however, and intended for communication to an artificial intelligence, the significance of a reasonable human observer’s interpretation is a matter of contention. And there is no such thing as a reasonable computer. Whilst the court can of course enlist the services of a professional coder to translate the code into human language, the process of interpreting that language remains the responsibility of the judge. Given that the logical architecture of computer code is different to that employed by human language, the task of interpreting that translation is simply not the same as the task of interpreting language intended for human understanding.[31]

The notarial practice could be substituted by the distributed ledger technology (DLT) which serve the same purpose as the notary public ensuring the authentication and voluntariness in entering into contractual relations involving real rights. However, there is a need to further legislate on these matters because rights are conferred by law, not by mere procedure. Another challenge to this will be the opposition lawyers will raise because this will definitely affect the legal profession and the authority to notarize documents.

Venue of actions can always be waived. A clear contractual stipulation can always take precedence over the procedural rules.[32] In case of transboundary transactions, the relevant doctrines under private international law (conflict of laws) shall be applied. Where a party committing a crime is a Filipino national Philippine courts can take jurisdiction. Jurisdiction shall also lie if any of the elements was committed within the Philippines or committed with the use of any computer system wholly or partly situated in the country, or when by such commission any damage is caused to a natural or juridical person who, at the time the offense was committed, was in the Philippines.[33]

VII. Recommendations

It is recommended that the Philippine Congress start crafting a law that specifically address the use of blockchain technology more particularly the use of VCs or cryptocurrencies in the emerging online market. This seemingly innocent technology is creeping into the Philippine commerce without any concrete regulation and penal legislation despite its possible impact on national economy. The current regulation imposed by the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas is not enough. There is a need for a law that ensures coercive and strict compliance.

The security mechanisms of blockchain is also a technology for other purposes such as authentication and trust related transactions. In utilizing the technology, it is also recommended that the rules on notarial practice be amended to cover a scenario where a notary public could notarize (electronic) documents under virtual presence. This is one step closer for the legal profession to catch up, if not level up, with the constantly evolving trends in technology and the law.

-=O=-